National Defence University–Kenya. (Photo: NDU-K)

Kenya has made a purposeful and sustained effort to create a culture of military professionalism within its armed forces since independence. This process has included continuous efforts to upgrade its professional military education system. It has been further supported by the active engagement of the Kenyan Parliament and provisions adopted in Kenya’s 2010 Constitution.

While every country’s path to establishing military professionalism is unique, Kenya’s ongoing effort to inculcate and strengthen a culture of military professionalism holds lessons that may be applicable elsewhere.

To gain a deeper understanding of Kenya’s experience, the Africa Center for Strategic Studies spoke with several current and former Kenyan officers to gain their perspectives on how the Kenyan Defence Force’s culture of military professionalism has evolved:

- General (retired) Robert Kibochi, former Chief of the Defence Forces (May 2020-April 2023)

- Lieutenant General (retired) Njuki Mwaniki, former Chief of the Army (November 2010-July 2011)

- Colonel James Kirumba, former student at the National Defense University in Washington, DC (August 2023-June 2024)

The following is a synthesis of those conversations.

The Emergence of a Culture of Military Professionalism in Kenya

Cultivating a culture of military professionalism has been a point of focus since Kenya’s independence from the United Kingdom in 1963.

Kenyan Defense Force airmen discuss classroom lectures. (Photo: DVIDS)

“The Kenya Defence Force (KDF) has had this culture of professionalism since right after independence,” explained General Kibochi. “We benefitted from a strong institutional legacy enabling us to establish the Kenya Armed Forces (KAF). A lot of young upcoming officers were trained at professional military education (PME) institutions abroad. And that foundation facilitated this culture of military professionalism being passed from generation to generation.”

General Mwaniki echoed this view, noting that “the culture of military professionalism in Kenya has emerged in parallel to that of our republic,” from the precolonial period to the colonial era, and then to independence. Since independence, he noted, the history of the KAF can be divided into two periods, the first from 1963 to 2010, and the second when a new constitution was adopted and the KAF became the KDF.

General Kibochi emphasized the KDF’s culture of transmitting the value of leadership from one generation to the next. “Everything is based on leadership. The leadership training has been the bedrock of this professional culture in the KDF. Each generation of leaders increases the level of professionalism from which they started. We call it a shared legacy—a shared legacy that what was started by my predecessor, I build on it and, when I leave the job, somebody else leads on it and continues.”

General Mwaniki and General Kibochi especially credited the reforms and legacy of General Daudi Tonje, who served as Chief of the Defence Forces from 1996 to 2000. General Tonje established the Defence Staff College as well as the Defence Forces Medical Insurance Scheme. He was also responsible for establishing the requirement that cadets at the military academy obtain a university degree prior to receiving their commission. Finally, General Tonje initiated the process of integrating women into the armed forces.

The Pillars of Military Professionalism in Kenya

Military professionalism in the KDF stands on three pillars, according to General Mwaniki. “The first one is character development, the second is fighting power, and the last one is professional military education.

Character development is the foundation of everything else that a professional military aims to accomplish.

“Character development is the foundation of everything else that a professional military aims to accomplish. This is the moral-ethical pillar of professionalism. It is the ability to do what is right as an individual and as a group. It is properly described by the word ‘integrity.’ Integrity has two meanings. The first meaning is the moral one: differentiating between what is right and what is wrong. To us in the Kenyan military, what is right is what is in the Kenyan constitution. What is wrong is acting outside of the constitutional authorities.

“The second meaning of the word ‘integrity’ is derived from the word ‘integer’—oneness or wholeness. Unity, camaraderie, communion, esprit de corps, and fellowship are indispensable to a national force. How transparent and honest and how conscientious you are to each other catalyzes mutual trust. Therefore, the first meaning of the word ‘integrity’ drives the second. The more honest we are with each other, the greater the fellowship and the higher the unit morale. Our operational oneness is also driven from that understanding of ‘integrity.’ The ability to do what is right as an individual and as a group is anchored on respect for the nation and its laws. It is the profession’s foundational structure.

“The second pillar is fighting power, which is the need and capability to fight. It consists of manpower, training, collective performance, and sustainability, among other factors.

“[The third pillar,] professional education, nurtures the framework of thinking within which you operate. This is relevant because it provides the theoretical justification for providing and employing the forces. The educational pillar provides commanders with the ability to understand the context and the world view within which they operate, and serves as the foundation upon which creativity, ingenuity, and initiative may be exercised in complex situations.”

Democratic Control of the Military

The 2010 Constitution defined Kenyan citizens as the sovereign authority where all power rests.

The officers all pointed to the importance of the 2010 Constitution in defining Kenyan citizens as the sovereign authority where all power rests. In this regard, the Constitution defines the KDF’s role and the framework for democratic control of the security sector. They emphasized the need to ensure that the entire force understands what this role means in practice, along with understanding the consequences for not respecting the values and norms enshrined in the Constitution.

“Allegiance to the constitution, subordination to democratic civilian authority, political neutrality, and respect for the rule of law have been inculcated to the extent that it is visible in every respect,” explained General Kibochi. “When you talk about respect for the rule of law, this is something that is well understood by the force. If someone goes against that, there are heavy penalties that they have to pay. Being apolitical is a very critical thing, for example. And if someone misses that train, you lose your commission or you are terminated with immediate effect. This ensures that you retain the neutrality that is so critical in a democratic environment.”

Professional Military Education’s Role in Transmitting Values

The officers all emphasized the role of PME institutions in transmitting and maintaining these values. According to General Kibochi, such schools are “the basis for inculcating the values of military professionalism, in terms of subordination to democratically elected civilian authority and allegiance to the constitution for example. When we talk about an NCO (noncommissioned officer) or an enlisted soldier or an officer who has given allegiance to the constitution, this is critically important. How do you expound that? You expound it through training institutions so they can understand what exactly this constitution is all about. ‘And how do I respect it, defend it, protect it? And why is it that we must subordinate ourselves to democratic civilian authority?’… All of this emanates from the constitution. Political neutrality—being apolitical—is one of the most critically important values that we have in the KDF.

Respect for the rule of law is critically important. … If you miss it at that early level, you will not be able to recover it in the future development courses.

“That must be taught at these PME institutions. Respect for the rule of law is critically important. People need to understand that right from the start. Especially when you think about the recruits that we get, civilians, from all over the country, from different backgrounds. You must try to get them into one cohesive entity that is able to align with these values. The training institutions, rightfully, provide the foundation for this. From the cadets in the Kenyan Military Academy to the enlisted recruits in the training schools, this is where these values must be inculcated. If you miss it at that early level, you will not be able to recover it in the future development courses.”

Colonel Kirumba emphasized that, “These values are actively taught and not assumed. This inculcation of values continues throughout a soldier’s career. Within the KDF, senior officers regularly engage in professional development programs that instill values of military professionalism and create opportunities for leadership development among their subordinates.”

Composition of the KDF and Military Professionalism

The composition of the KDF is crucial to its professionalism, the officers all agreed. Maintaining regional balance among the force through the principle of inclusivity is required by the 2010 Constitution, from the lowest levels all the way up to the chiefs of the various services. General Mwaniki elaborated, “You must be very sensitive to the rainbow because we are a rainbow nation. You must promote national unity and protect it.”

“While recruitment spans across tribes, ethnicities and genders,” Colonel Kirumba explained, “by implementing merit-based recruitment and promotion practices, the KDF benefits from professionalism, integrity, and effectiveness. This approach has helped to establish a military leadership that is accountable, competent, and aligned with the values of the broader society it serves.” Toward this end, the KDF has elevated the importance of clear promotion standards to enhance its professionalism over the years.

A Kenyan Army engineer negotiates with foreign military forces role players during a civil affairs field training exercise.

There are also strict quotas setting the ratios of NCOs to soldiers and officers to NCOs. There are also limitations on the number of general officers in the KDF. These guidelines help keep the force lean and effective. General Kibochi also emphasized the importance of ensuring women are properly integrated within the force, as required by the Constitution.

Professional Military Education Institutions and the National Defence University-Kenya

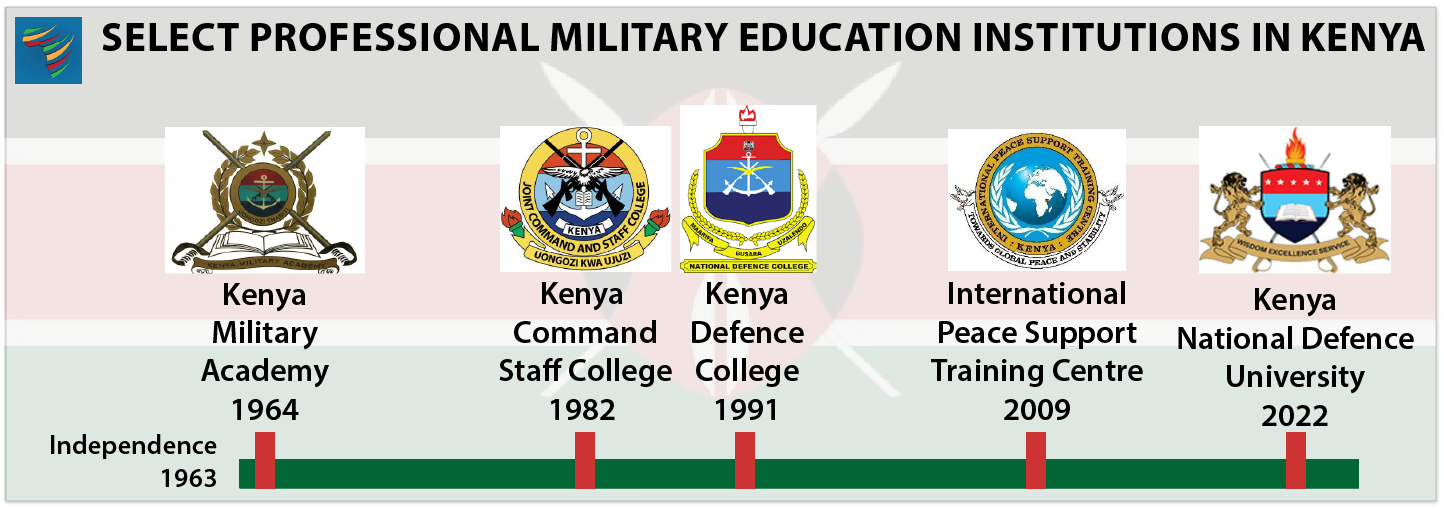

Kenya’s multiple professional military education institutions play a vital role in building the force’s professionalism. The country’s first military leaders played a key role in building these institutions in Kenya. This includes obtaining the facilities, such as land and barracks, and ensuring they would run properly and could eventually be expanded. This began with the Armed Forces Training College in 1964 (which is now the Kenya Military Academy). This was followed by the establishment of the Command Staff College in 1982, the National Defence College (NDC) in 1997, and eventually the National Defence University, which was chartered in May 2021 as a specialized university for training, command education, and research in national security and strategy.

The decision to establish a National Defence University-Kenya (NDU-K) was made in 2010/2011, leading to its official opening in 2022. According to General Kibochi who was Chief of the Defence Forces (CDF) during its opening, “The NDU-K affirms that strategic planning and critical thinking are the hallmarks of operational art and statecraft,” notably through the establishment of its Center for Strategic Studies.

While Kenya had long opened its PME institutions to regional partners, particularly in the East African Community, Kenya’s growing role in international peace support operations in the region and the continent proved a catalyst for bringing these institutions together under the umbrella of an NDU.

This has become a major exporter of professionalism into the peacekeeping missions across the continent.

This has been integral to promoting professionalism and peaceful relations, both at home and across Africa. General Kibochi recalls how, because one of his Defense College classmates similarly rose to chief of his country’s defense forces, their collegial relationship helped to address cross-border challenges peacefully and professionally when they arose.

Given Kenya’s expanding role in peacekeeping, establishing the International Peace Support Training Centre was essential to professionalizing peacekeeping. As General Kibochi explains, “General Tonje believed that you cannot just wake up one morning and send a group of soldiers to undertake peacekeeping without having gone through a professional training. Today, we have one of the largest peacekeeping training institutions on the continent, training not only the military but also the police and civilians. This has become a major exporter of professionalism into the peacekeeping missions across the continent.”

The Role of Noncommissioned Officer Schools

According to General Kibochi, “The hallmark of any force is the NCO cadre. This is why the KDF established an NCO academy working closely with the United States Army. If you expand education for the officer corps at the expense of the NCOs, then you have a gap of knowledge. Since all officers must graduate with a degree from the Kenyan military academy, if you don’t have NCOs also graduating with a diploma or first degree, then you have this gap. And this gap creates a lot of challenges when it comes to the knowledge of a changing operating environment.”

Sustaining Norms and Values of Professionalism

Inculcating norms occur through leadership at all levels of the force. General Kibochi reflected, “When you don’t have proper leadership at every level—not just at the senior level but right through all levels—it is very difficult to professionalize. Because professionalizing means that every leader at all levels must be able to develop those who are under them. So, as leaders exit, new leaders have been prepared to fill the gap. Leadership is the glue that really holds it all together. I think that challenges probably start from the foundational training that young leaders get, whether you’re talking about enlisted or officer cadets.”

An important aspect of the KDF’s professionalism, according to Colonel Kirumba, is its robust military justice system because it is “responsible for ensuring discipline, accountability, and adherence to legal standards among military personnel…. By addressing unethical behavior and enforcing consequences for wrongdoing, the military justice system helps deter future misconduct and maintain high standards of professionalism within the armed forces.”

Effective Civilian Oversight

General Mwaniki remarked, “The most critical [factor to professionalism] is the checks and balances” including parliament, civil society, and the private sector. “The latter two are especially relevant because while parliament represents the people, civil society and the private sector are composed of citizens themselves, so their role is crucial.”

General Kibochi added that, “Parliamentary oversight on defense matters, including budget requirements, recruitment, and integrating women into the force is undertaken on a regular basis.”

Kenya Defense Forces combat engineers training. (Photo: DVIDS)

In addition to hosting programs at the NDC for members of parliament sitting on committees that deal with defense and foreign relations, another way of ensuring that there is close interaction between uniformed military officers and civilians, according to General Kibochi, is “to have civilians participate in PME institutions, either as visiting lecturers coming to speak about issues of democracy and the rule of law, or attending the institutions themselves. At the National Defence College, one trains together not just with KDF officers, but also with National Police officers, as well as civil servants in various ministries.

“When you train together, including by participating in exercises where officials practice the implementation of the national security strategy, it’s very easy to start creating the culture of senior leaders in different environments who can, together, look at the national interest, rather than institutional interest. This has worked extremely well where a number of civilian professionals have attended training at the National Defence College.”

Military Professionalism Facilitates Whole-of-Government Approaches

“The other thing we’ve realized,” General Kibochi explained, “is that because of the change of the threat environment, multiagency cooperation, this whole-of-government approach [is increasingly essential]. An asymmetric threat can never be fought just by one institution. So, how do you institutionalize multiagency cooperation? Over time, we’ve had to develop a multiagency strategy with well-defined approaches for undertaking multiagency operations. We now have a national security strategy which really orchestrates all these strategies and policies.”

Measuring Success

According to General Kibochi, “You can measure success of defense forces through their leaders. This is especially true today when you have a very decentralized operational environment. When you talk about asymmetric warfare, you’re not talking about a brigade having to go and fight, you’re talking about a young lieutenant who is sent with his 30 or so men and women to undertake a task. The success of any operation is dependent on leadership at the lowest level. If these young soldiers at that level have no character, then obviously you will not deliver on the mission.

The success of any operation is dependent on leadership at the lowest level.

“Military professionalism is about the standards of delivery on the missions and tasks that are given. So, it’s so important that we build leaders of character from the lowest level upwards. When we operate in places like Somalia, during my tenure as CDF I would visit some of the forward operating bases. And I would find a young major who is hardly 35 in charge of about 200 men and women. After listening to them, you get out of there very satisfied that, no matter what happens, this young leader will be able to achieve the mission. And because of the training that he’s gone through, he’s confident that he can deliver without hesitation.”

Colonel Kirumba suggested that “the many countries that send their militaries to come and train in Kenya is also an indicator of success. That and the fact that PME graduates are subsequently successful in their jobs are strong markers of progress.” He added that “the fact the Kenyan military has been entrusted to lead important international missions, such as the East African Community Regional Force in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the United Nations mission in Haiti, are further recognition of this growing professionalism.” While still an evolving process, Kenya’s next generation of military leaders hopes to build on these lessons to further elevate the effectiveness of the KDF as a professional force.

Additional Resources

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Creating a Culture of Military Professionalism in Senegal,” Spotlight, December 6, 2023.

- Dan Kuwali, “Oversight and Accountability to Improve Security Sector Governance in Africa,” Africa Security Brief No. 42, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, September 2023.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “The Role of Parliamentary Committees in Building Accountable, Sustainable, and Professional Security Sectors,” Spotlight, April 3, 2023.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Deepening a Culture of Military Professionalism in Africa,” Spotlight, December 20, 2022.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Professional Military Education Institutions in Africa,” Infographic,February 25, 2022.

- Kwesi Aning and Joseph Siegle, “Assessing Attitudes of the Next Generation of African Security Sector Professionals,” Africa Center Research Paper 7, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, May 2019.

- Emile Ouédraogo, “Advancing Military Professionalism in Africa,” Africa Center Research Paper No. 6, Africa Center for Strategic Studies July 2014.

More On: Military Professionalism